So then, to refresh what we learned from Part One, it had a lot to do with being a lazy young fellow, and looking towards a profession that would allow for that. Laziness wasn’t a defect to be overcome (though my father and many others thought so), it was a quality to be accommodated into the design.

And let’s not be mistaken that my laziness kept me from getting jobs, and doing a good job. Like the hero of Heinlein’s story, I wasn’t looking for a way to get by while others pulled my weight for me, as too many do in this and in every age. I looked for ways to do things better, with greater efficiency, and without wasted time and effort.

I had paying jobs since before I was legally allowed to. And no one can work on an asparagus farm (including running it on my own for two years when my father took up the golfing circuit in a more serious way) without doing a herculean amount of physical labor.

But as a goal it was preeminent in my long range plans.

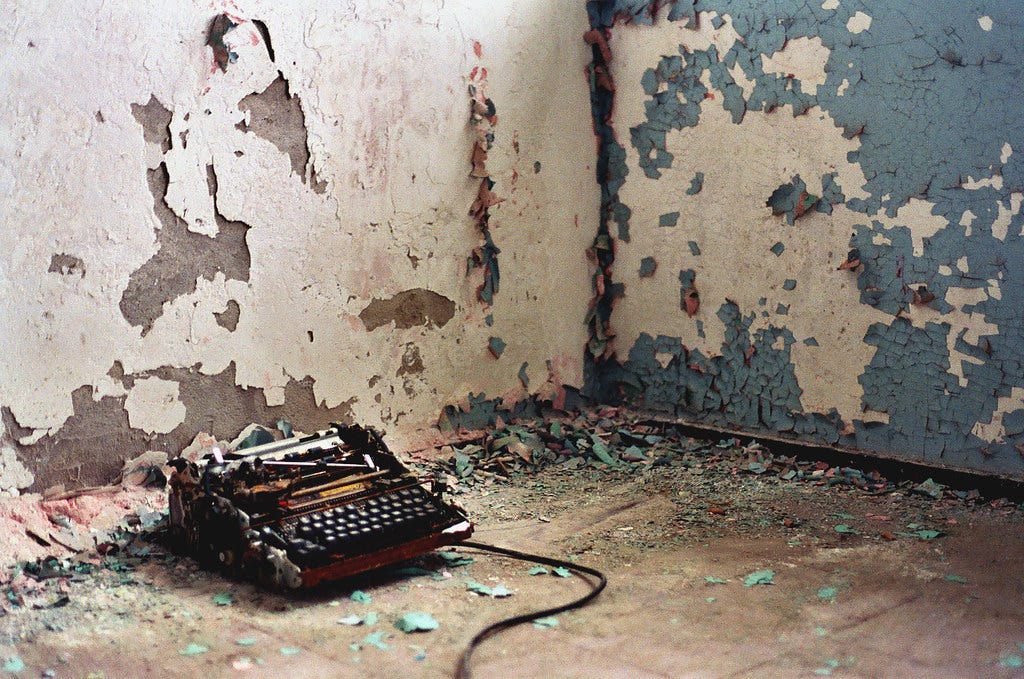

Learning to Spin a Tale

But there were other influences and inspiring incidents at work in my formative years. Many, in fact. I’ll tell you two of them.

In 1962 I was five years old. We were stationed in Germany (a young kid’s paradise. How many of you had the ruins of castles to play in, in your back yard?) when my father decided to finally retire from the Army (which I only much later learned was largely due to the Cuban Missile Crisis, which had just taken place and which nearly resulted in Germany being the central battleground of a Third World War). We would be returning to the states, which I only vaguely remembered.

At a family meeting about the coming move my mother announced that we would be coming to America via New York City. She excitedly proclaimed we would see many wonders there, including skyscrapers. All of the family was excited at that prospect. At five I had no idea what skyscrapers could possibly be and apparently didn’t ask. I tried to work it out on my own, and the best I could come up with was skyscrapers must be giants who scraped the clouds with huge squeegees to cause rain. That seemed reasonable and yes, I was very excited to see such things.

Fast forward to the boat crossing, upon the USS Buckner, watching our Pontiac station wagon lowered to the docks on a crane, and finally driving through New York City.

“Barbara, can you see the skyscrapers?” Mother said.

“Yes!” said Barbara, with undisguised wonder.

“Peter, can you see the skyscrapers?” Mother asked.

“Yes I can!” screamed my older brother.

And on down through the ranks of all of the Willingham kids, until she got to me.

And then, when it was my turn, “Billy, can you see the skyscrapers?” she asked. But I couldn’t. No matter how I tried, frantically looking for the giants with their squeegees, all I could see were tall buildings in every direction.

So I said, “No. All these buildings are in the way.”

It brought the house down.

The entire car, packed to the gills with Willinghams, laughed long and loud, at something I’d said. Even my father, who never laughs at anything, laughed so hard he nearly drove us into oncoming traffic.

I had no idea what I’d said that was so funny, but for one sweet moment I was the center of attention, in a good way, and I liked it.

I wanted more of it.

(Yes, I quickly learned what a skyscraper really is, but that isn’t the point now, is it?)

The Second Example

In seventh grade, attending the McKnight Junior High School, I was stuck every day in a two-hour language arts class, jointly taught by Mrs. Mathewson and Miss Pringle. It was supposed to be two one-hour classes, covering an array of subjects, but, without quite getting permission, the two teachers opened up the room dividers between the two classes, doubled the time, and taught it together.

One of the assignments during that year was a two-week span of writing a daily journal chronicling our lives. I found the idea dull, mostly because I seventh grader in a sleepy suburb of Seattle leads a very dull life. So I decided to punch up the material a bit, stealing ideas from TV, books, comics, and any other source that passed my way.

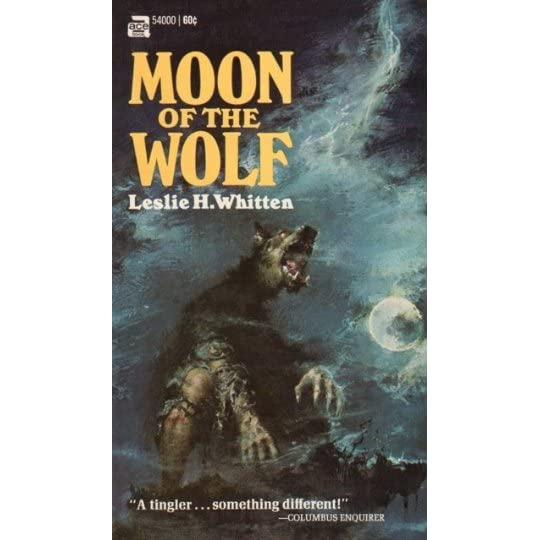

I started my daily journal about how my Uncle Bob would be coming over to our house tonight, to be chained up in the basement, during the full moon, during which time he’d transform into a werewolf. I wrote about the feeding protocol and how we had to carefully inspect the chains to make sure he hadn’t loosened them, so he could grab us when we wandered too close with his supper dish.

Then I wrote about how I accidentally found the pod in our garage, in which the alien thing that had replaced my father was grown.

No, I wasn’t nearly that clever. My pal Bruce Givan had just shown me the Phillip K Dick story The Father Thing, which he’d snagged out of the school library, and I ripped the story off with shameless abandon.

And I wrote about selling my brother to the fairies, and about his less than perfect replacement changeling. And I wrote about how my older sister Barbara would disappear at night to rule over the high fantasy kingdom she was chosen to rule, and about the coming war to keep her on the throne. And then there was sister Penelope’s vampire problem.

And so on. I spun out whatever nonsense I could think of, or steal from other sources.

And I kept waiting to get into trouble for not doing the work as assigned.

Instead, at the end of the two-week period, Mrs. Mathewson announced that the assignment was done and everyone could stop writing their daily journal, “Except for Billy Willingham, who has to keep writing his every day.”

And so I did, until the end of the school year, enjoying the notoriety every week or so as my journal entries were read aloud to the class.

Those were but two of the many incidents during my upbringing that made me think I could make a go at spinning tall tales, if not professionally, at least as an avocation.

I liked knowing I could capture the attention of one or more audience members and hold it for as long as I wanted to do so. Well, at least sometimes I could do that. More often I failed — but that’s what we do. We keep at what’s important to us, until we get better at it.

Someone said, “The definition of insanity was doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

I disagree. I think it’s a fine definition of practice though. Or maybe call it training.

Over the years, amidst all of the other distractions and duties of life, I worked at spinning fun and bizarre stories until I got better at it. A little bit at a time.

Gradually I also got a wee bit better at coming up with my own bizarre stories, stealing less from other folks and their stories.

Summing Up

So far it’s been a mix of laziness and ego gratification fueling this journey towards writing as a career. Of course there needs to be more than that, added to the pot, to make a go of it over the long term: the need to find a way to get paid for it, for example. We’ll take that up someday soon in Part Three.

Your dad was a pro-golfer?

Another great post!