Why I Write - Part One

In which the votes are in and this is what you most want to know about, two votes more than the history behind Batman vs. Bigby, taking into account the allowed ballot box stuffing.

Part One — The Bum

Why I write — specifically why I chose to pursue writing as a profession — is a surprisingly difficult question to answer, because there are too many origins to the story. Too many origins to count, in fact, but we’ll try to isolate some of the bigger moments of career inspiration.

First of all, let’s start with the earliest of the many motivations. Early on in my life — we’re talking two or three years old (yes, I was a bit of a savant) — I realized I was a lazy fellow. I wanted to do the least possible to get by. And I also realized, with the power of the most absolute of absolute epiphanies, that I was never going to change. I was never going to grow out of it. In fact, I knew even then I would grow more into it than out — so in that sense at least, I was going to change. I was going to become better and more intractable in my chosen destiny.

For context let me tell you that my parents were anything but lazy. Both had grown up in the hardscrabble mid-wars years (between World Wars One and Two) on working farms (I’m not sure hobby farms even existed back then), where the day began before sunup and lasted past sundown, with a break for schooling, but that was in addition to one’s workday, not a replacement for it. Both mother and father were early inculcated in a strong work ethic that never faltered throughout all the years of their lives.

After her farm forged childhood, on the eve of the Second World War, my mother, Hazel Mae Horner, delayed (permanently, it turns out) to go to work in The Manhattan Project — yes, THAT Manhattan Project. Specifically she worked in Eastern Washington’s Hanford Atomic Reservation, where all of the fissionable material for the Project was created? Refined? I’m not sure what the proper term is. To her dying day she never revealed exactly what she’d done in that place, but I got the impression it was always hard work and it took her through the war years and for a few years beyond.

Then she went back to the family farm while getting her secretarial training at a trade school, through a version of the GI Bill. Sometime after that she met my father.

My father, Benjamin Thomas Willingham, missed serving in the Second World War, but not by much. His older brother William (after whom I was named) served and died in the Attack on Pearl Harbor. My dad joined the Navy, served for one hitch, then transformed to the Army, where he served as a lifer, until retiring as a Master Sergeant in 1962. Sometime along the way he married my mother and legally changed his name to Thomas Benjamin, swapping out the two given names.

I was born in there too, along with a small battalion of older sisters and one older brother. After the Army, our family left Germany, his last station, and headed back to America, and as far west as we could go, without getting on another boat, settling in the Seattle area. My father worked construction, until he fell off a building, and then started a janitorial and carpet cleaning business, which he built up into a pretty big company, until mom and dad, missing their farm days, sold it all and bought an asparagus farm in Eastern Washington. After a half dozen years, perhaps recalling how tough farming was, they sold the farm. Dad went back into construction.

During that time my mother kept the large household and did the accounting for many businesses.

Have I made my point yet?

My parents were no strangers to hard work.

So then, how did I turn out to be so much unlike them? Truth is, I don’t have a clue. If I’d grown lazy in my teenage years I’d pass it off as stereotypical teenage rebellion. But no, I realized early on what sort of fellow I was going to be, even in those formative years in which I admired my parents without reservation.

Let’s take it as stipulated then. In the midst of a hard-working family, I was, and fully intended to be, a lazy bum.

What kind of life can a lazy bum look forward to? I had few ideas. I knew that bums got to dress in rags and carry all of their worldly possessions in bindles on sticks. That was kind of cool. They didn’t live anywhere in particular, but traveled the rails and went wheresoever they wished, and that was way cool.

About two years after my folks left the military, and we’d been in the Seattle area all that time, I asked them when we would be moving again. I grew up moving bases every year or two, and I guess it had stuck. In most of my adult life I suffered extreme wanderlust and continued to move every few years, which I could do as a writer, carrying my job with me, so maybe that had something to do with my chosen profession.

But that wasn’t it. Not entirely. Not even mostly.

Let’s get back to the “how to be lazy and still not starve” conundrum.

Early in my childhood, among a gaggle of kids talking over what we wanted to be when we grew up, one of my best friends, named Bruce Givan, once told me, “There are jobs where all you have to do is sit in a room and think.” I’m not sure I believed him. That seemed too wonderful to me and I couldn’t figure out why anyone would pay someone to do nothing but think. But I didn’t entirely not believe him either, because I very much wanted to live in such a world.

One of my favorite TV shows at the time was The Dick Van Dyke Show, which I was able to enjoy in its original run. Dick Van Dyke played a fellow named Rob Petrie, who wrote for TV. He worked in a writers’ room with two other comedy writers, by the character names of Sally Rogers and Buddy Sorrelle. Their standard workday was this: Rob would exercise, usually doing pushups, whilst calling out ideas for whatever sketch they were doing. Sally would man the typewriter, typing up the others’ ideas while contributing ideas of her own (and this was the most like real work of the bunch, so boo on poor Sally). But, and here’s the best part, Buddy would stretch out on the couch and call out ideas from his prone position.

Buddy Sorrelle quickly became my hero and my inspiration. Here was the closest job I had ever seen to Bruce Givan’s revelation about the job where all you had to do is think. And Buddy got to do it lying on his back all day, even napping from time to time.

Sure he had to actually voice his ideas, but I could do that much. Thinking, and occasionally talking, while lying on a couch, and getting paid for it — that was the dream.

Glorious, lazy Buddy was a writer. So that planted (perhaps the first) germ for me to consider being a writer as well.

That solidified my goal at the time: to work in a writer’s room, for a TV show, where there was a Sally to do all of the actual typing and composing.

Since then I’ve always wanted to work in a writing room, but never got offers. Let me take a moment to shake my fist at all of my comic-writing colleagues who have gotten the call.

The closest I ever came was during the time I was writing Robin for DC. There was a one-week writing room in which I, along with a thuggish gang of comic book writers and editors, all from DC’s Batman Group of books, gathered in New York to hammer out the details of the big Batman crossover called War Games. It was pretty cool. Bat Editor Matt Idelson wrote everything down on the big board, so all I (along with the others) had to do was sit back and call out ideas. Our food was brought in (just like Dick Van Dyke’s TV writing room — but sadly not delivered by a young Jamie Farr in his first regular TV role). If there had been a couch in the room to stretch out on, it would have been the full Buddy dream job.

But I digress.

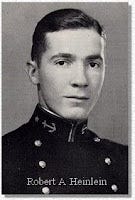

Now let’s talk about another writer of note. His name was Robert Heinlein and you know his name (or you should) and his work (or you should). I read most, if not all, of Heinlein’s work, including one of his short stories called: The Tale of the Man Who Was Too Lazy to Fail.

It was a story very loosely based on Heinlein’s own life, especially his service in the US Navy, and, in addition to being an entertaining tale, it was a lovely tutorial on how one can be lazy but still succeed in life, by also being smart. It ends up with the fictional character being too lazy to fail, fully justifying the title, until he retired as a millionaire. If you’ve never read it, I urge you to seek it out.

This story struck me as another solid sign that one can indeed be lazy in life, but do it successfully, and maybe not be a bum.

And here’s the thing. Heinlein was also a writer.

The connection between laziness and the writer’s profession was well and truly established.

Why do I write? To a very large degree, because it fits my lazy ways. But that isn’t the only answer, or at least not the full answer.

Next I’ll talk about the other influences that led me down the writer’s path.

This was incredibly entertaining and nice to read.